Education reform should not remind me of The Great War. Yet I see a vast wasteland of vitriolic trenches dug deep through the annals of reading research. Battalions of reading experts have barricaded their positions behind barbwire as toxic tweets roll across a devastated wasteland of civic engagement.

On one side you have those who wrote and support the Common Core State Standards who argue for increased text complexity. These scholars and pundits latch on to the idea American scores on international assessments must mean previous efforts and documented research in comprehension must be wrong. They note that the level of text complexity high schoolers read has steadily declined since 1984 (interesting the same year the standards movement was born).

On the other side you have teachers who cling to their approaches to reading instruction. They reject almost anything that favors the Common Core State Standards. They draw connections from the Common Corse State Standards to corporate interests run by the oligarchs in the Gates Foundation, The Broad Foundation, and ALEC.

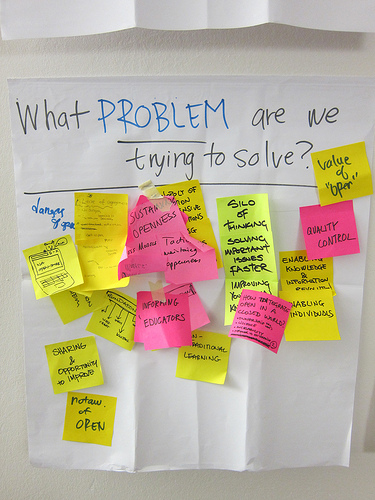

In this discussion of text complexity and reading instruction both sides miss the single greatest shift in literacy practices in human history. As we evolve into a network society (Castells and Cardosa, 2005) we must recognize socially complex texts not simply lexile levels or instructional leveled texts.

Accountability Based Reformers

Accountability based edreformers believe we need new approaches to reading as our low PISA scores must prove that strategy instruction and readers’ workshop do not work (they do not mention what happens to international benchmark scores when you control for poverty).

Those on the more conservative side of edreform argue that along with text complexity we need to focus on building Hirsch’s idea of cultural literacy. They stress over and over again the role of content knowledge.

The accountability reformers have come out swinging against Caulkin’s flavored balanced literacy and readers workshop. They cite Tim Shanahan (who has argued against leveled texts long before the Common Core). Every time they testify before a state government in support of the CCSS the conservative edreformers stress how the CCSS require students to read the America’s founding documents over and again.

What they get wrong

We do know that after decoding ability background knowledge is the leading predictor of reading comprehension. (Paris & Stahl, 2005). Even early reading researchers from Gates (1931), Huey (1908), and Gray (1939) noted the relationship between background knowledge and reading. Content knowledge does matter.

Yet so does motivation and choice. In readers’ workshop students get some degree of flexibility in choosing what they read. Some edrefomers bemoan this activity and state it only works for the middle and upper class. They want a common read in the classroom. The idea that choice should only be available to those born in brownstones rather than those born with brown skin does not sit well with me.

We know that agency, engagement, and motivation matter when teaching reading. In study after study engaged readers outperform less engaged peers (Guthre & Wigfield, 2000). Yet the Common Core State standards do not mention reading for enjoyment. Not once. The standards do not cite motivation when selecting texts. In fact texts should be selected using some convoluted heuristic that usually just boils down to lexile scores.

We also know from three decades of research that strategy instruction works (Duke & Pearson, 2005). Yet many CCSS supporters attack strategy instruction as a vapid content free approach to reading comprehension. They have called for an end to pre-reading activities. They only want close reading which derives from a philosophy that views all meaning “contained within the four corners of a text” (David Coleman, author of the CCSS). Granted the effect size for strategy instruction (specifically reciprocal teaching) is much larger for less proficient readers than more skilled readers but shouldn’t that be an even greater reason to keep strategy instruction in our neediest schools?

The Opposition

Those who oppose a view of reading instruction that revolves around text complexity and lexile levels cling to approaches that level texts for students as part of instruction. To be clear this is not the only form of reading instruction included in balanced literacy classroom but it is part of the daily routine. These advocates cite the work of Carol Burris and Fountas and Pinnell.

In these approaches the teacher provides a mini-lesson (usually some strategy instruction) and then students go off and read books at their “independent level” while the teacher provides guided reading lessons at students “instructional level.” Students can choose their books, but within a limited range that is often dictated by a computer program.

What they get wrong

Students are more than a number or letter. The idea that choice must be limited based on how well a student performs on very imperfect reading inventories simply does not make sense. I have seen many students engage in texts well above their reading level because the topic is of interest. Like the accountability based reformers the opposition also discounts motivation (albeit to a lesser degree).

These educators must recognize the importance of building background knowledge and enculturating students into the discourses that are favored by academia. When instructional minutes are precious teachers may have to recognize that independent reading is not always the best use of time nor the fastest approach for developing background knowledge.

What They Both Get Wrong

Both approaches to text difficulty ignore our shift from page to pixel. The Common Core State Standards do mention technology and call for media skills to be taught across all subjects (CCSS, 2010, p. 4) but when you read the anchor standard ten about text complexity you will find no mention of new media skills or socially complex texts.

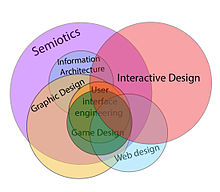

Henry Jenkins et al. note that “literacy is no longer a set of personal skills; rather the new media literacies are a set of social skills and cultural competencies, vitally connected to our increasingly public lives online and to the social networks through which we operate” (Jenkins et al., 2013 location 1177). We need to redefine text complexity to account for socially complex texts.

Socially Complex Texts

I define socially complex texts as concurrent arguments that unfold in print and social media with varying degrees of authority and amplification. Basically socially complex texts are authored by opposing perspectives discussing an issue often with equal passion and mutual disdain.

In order to make meaning with socially complex texts readers have to engage in network fluidity. These ideas often have a definitive volume, their is weight attached to them. In fact the volume of texts around any issue is limitless. Yet these texts have no shape. They do not exist in silos.

Take the debate around text complexity. It is a perfect example of network fluidity and socially complex texts. Readers may have to travel to a Fordham blog, read comments on the Bad Ass Teachers Association Facebook page. They might follow the #CCSS and #edreform hashtags on Twitter. Their RSS feed is hopefully diverse and includes both perspective. They may even follow citations back to Google Scholar.

Reading in Fluid Worlds

How do we prepare students to swim in the meaning found in such a fluid environment? We have to go well beyond the positions staked out by those who support and oppose the Common Core. We need to look at #connectedlearning. Through agency, engagement and academically focused interest driven production we can teach students strategic text assembly.

Reading is no longer a closed event. Especially when we are engaging in civic discourse and activism. Students need to know how to evaluate and try out different perspectives. They need to understand and develop routines for managing external storage devices and having access to the history of human knowledge.

If educational reform debate pigeon holes the reading debate behind the battle lines of text complexity, close reading, and content knowledge then we have already lost the war

image credit: No man’s Land. Public Domain. Wikipedia.